Introduction to clinical variant interpretation

Scene setting

- Accurate diagnosis

- Familial Screening

- Inform prognosis

- Personalized treatment

Overview of Rare Variant

1 million variants per person

~1% are protein-coding

Finding one variant that causes a disease is like finding a needle in a haystack.

Overall aim

PathogenicLikely pathogenic- Unceartain significance

- Likely benign

- Benign

Clinically actionable

For each variant:

- Have we

seenit before? - What do we

knowabout it? - What can we

predictabout it? - What new

datawe added?- From this

family Experiments

- From this

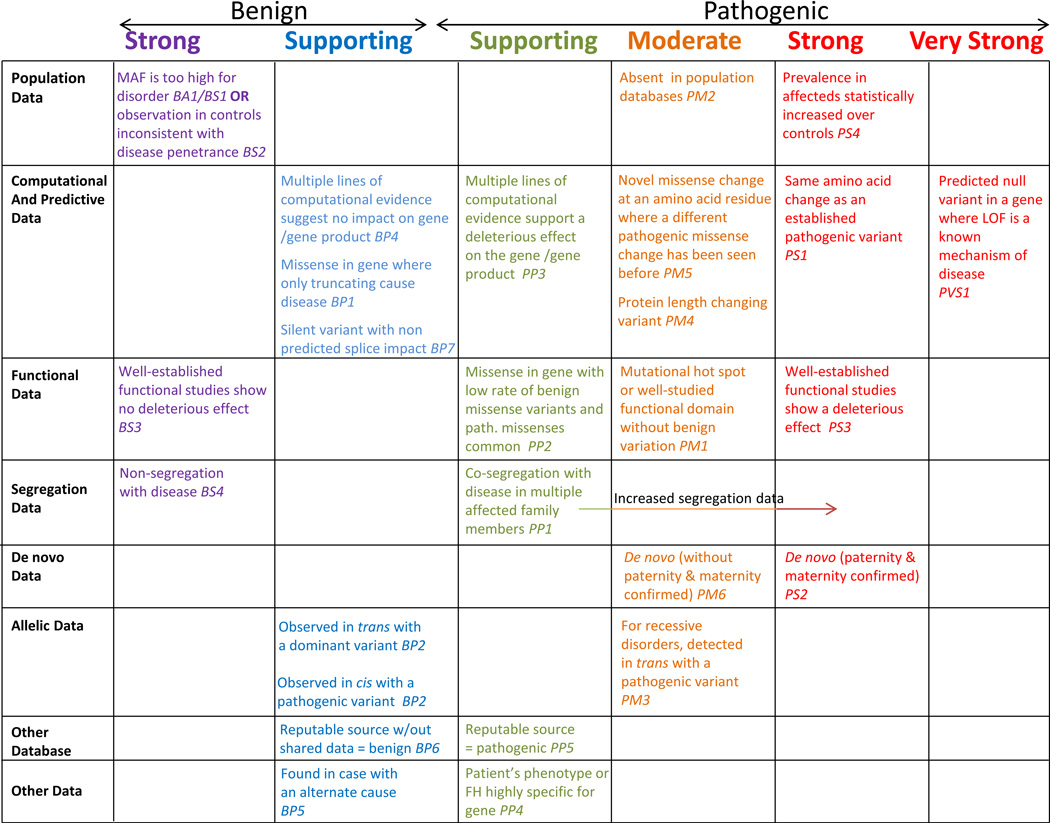

ACMG/AMP guidelines

A Bayesian framework

- Start with a

priorprobability - Modify it with set of

odds, orlikelihood - Get a

posteriorprobability

Pathogeneic: posterior probability > 0.99

Likely pathogenic: posterior probability > 0.9

Uncertain significance: posterior probability 0.1 - 0.9

Choosing a prior:

- Variant in small panel testing / large population screening

- In the range for VUS

- Use 0.1 (Empirical for BRCA1/2)

Advantages:

- Incorporate Benign and Pathogenic in one step

- Can compute odds of pathogenicity for each rule strength to test against functional assays or other metrics

- More flexible

Evidence

Variants in patients

Similar phenotypes

How many variants?

Patient denominator is often unknown

Very unbalanced sample sizes

Use ClinVar to find variants that have been seen

before.

Some cautions on using ClinVar data:

- Bias in certain genes and variants types

- (Likely) Pathogenic variants are more likely to be submitted

- Unclear about variant classification

- Historical 'literature` only curations

- Data not versioned - classification can change

Functional Data:

Matchmaker exchangeLitVar- PubMed

Segregation Data:

Segregation with one or more families

Caution:

- reduced penetrance

De novo occurrence

In controls:

- Healthy, or population

- At what frequency?

Allel frequency is one of the strongest predictors of benignity, but is not an indication of pathogenicity.

Population datasets:

gnomAD,UK Biobank

Not disease free, expect disease frequency at the same rate as the general population

Allele Frequency (AF)

\[\text{AF} = \frac{\text{number of alleles with variant}}{\text{total number of alleles}}\]

Dominant Disease: < 0.1%

Recessive Disease: < 1%

The proportion of individuals with a variant that develop the disease

is the penetrance.

Penetrance:

- Measure on variant or gene level

- Often difficult to measure

- Threshold of disease

familybased measures areoverestimatesbiobankslikelyunderestimates- variants are often very

rare/ unique to individual families

Disease-specific statistical approach:

A penetrant dominant mendelian disease

\[\text{Max AF} = \frac{\text{Disease Prevalence} \times \text{heterogeneity}}{\text{Penetrance}}\]

Heterogeneity: maximum proportion of disease attributeable to single variant

Popmax filtering AF (FAF):

Highest allele frequency in any population

if Popmax FAF > Max AF = Too

common

Limitations:

- Low converage: absence does not mean rare

- Ethnicity: founder variants

Other evidence

Highly specific phenotypes that matches gene

Observed in trans with known pathogenic allele

Similar to previously reported pathogenic variant

Future direction

Moving towards a points based system

Confirming and refuting disease-gene links

GenCC can be used to know the gene and variant that

relates to a disease.

PanelApp: Red, Amber, Green

- Red: No evidence

- Amber: Some evidence

- Green: Strong evidence

Experts review the genes and classified to the above categories.

Can be used to determine which variants are diagnostic candidates.

ClinGen: Literature only curation of variants

Burden testing can be used to determine if a gene is associated with a disease

- But

- Need large sample sizes

- Uniform phenotyping

- Well matched controls

- Normally limit to rare variants of a particular class

- Small genes may not be significant

- Many false disease-gene claims are made

Good Example:

MYH7in dilated cardiomyopathy

significat in ClinVar, Genebass, GenCCBad Example:

CTNNA3in ARVC

OMIM disease association

Limited evidence in GenCC and Genebass

Three classification in ClinVar in gnomAD, many VUSs, limited evidence

Conclusion:

- Many disease-gene links are not well supported

- There are many resources to help determine the strength of a disease-gene link

Measures of variant pathogenicity and genetic constraint

Variants with less frequently are more likely damaging.

Modelling mutation rates

To detech genes, regions of genes, or variant types that are under constrained or depleted of variation.

Detect shiftsin allele frequency spectrum (deleterious variants are rare)Measureadepletionof variants compared toneutralexpectationConservation:

- Comparison across species (position, region, gene throughout evolution)

- Requires small number of genomes from different species

Constraint:

- Within human measure

- Detect Human regions

- large number of human genomes

???????????????????????????????????????????????????????

Mutability adjusted proportion of singletons (MAPS)

Used to detect the shift in allele frequency spectrum.

More loss-of-function variants should have higher proportions of singletons.

some genetic context is more mutable than others.

Example: C>T at methylated CpG sites

\[\text{MAPS} = \frac{\text{Observed singletons} - \text{Expected singletons}}{\text{Observed variants}}\]

Useful for well-known variant classes

Measuring LoF compared to expected

A mutational model for predicting number of variants

Gene level constraint metrics

LOEUF: rank all genes to tolerance to LoF variants, low score indicates

haploinsufficiency.Regional missense constraint

MEF2Chas a N-terminal DNA binding domain- Missense variants in this region cause Developmental Disorders

Amino acid level constraint

Non-coding constraint

It is useful for dominant early onset phenotypes

Example: BRCA1

But:

- Ignore some variant contexts

- Resolution is limited

Can't assess individual variants

Individual variant pathogenicity

Majority predicting the deleteroiousness of missense variants

SIFT / Mutation assessor / GERP: sequence and evolutionary conservationPolyPhen2: Protein sequence and structureMutPred/Mutation taster: Machine learningREVEL: Ensemble of predictors

Others:

SpliceAI: Predicts the effect of variants on splicingCADD: Genome-wide tools

All these tools are

supportinglevel in ACMG/AMP guidelines, meaning they havelimitedevidence

Generally, REVEL for missense, SpliceAI for

splicing, CADD for Genome-wide

Conclusion

Computational tools are useful to determine genes/regions/variant types that likely to be deleterious

Predicting the deleteriousness of underlying data including constraint and cross-species conservation

Used with ACMG/AMP guidelines

Glossary:

Dilated Cardiomyopathy: a condition in which the heart becomes weakened and enlarged and cannot pump blood efficientlyVUS: Variant of uncertain significanceARVC: Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, a genetic disorder that affects the heart musclehaploinsufficiency: a condition in which a single copy of a gene is not sufficient to maintain normal function